Welcome back to Registering the Registry, where we consider and review the films inducted into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry by merit of their cultural, historical, and aesthetic qualities! Today, as we discuss 1970’s Requiem-29 from UCLA’s Ethno-Communications Program, we will cover an oft-overlooked corner of Los Angeles history, process the facts of police brutality and subsequent cover-up, and question what can be done when the systems behind these remain in place decades later. I cannot pretend this will be a fun piece, but I do hope it proves accurate and informative. Let’s begin.

***

Today’s film places us in something of a limbo state. It once again covers an important event in American history largely untouched by the public education system despite its importance in the development of the larger Civil Rights Movement, a topic likely unknown to most except those who care to specifically research this subject. Sources external to the work itself place it as a creation of the UCLA Ethno-Communications Program under one David Garcia, but the film itself contains no credits whatsoever, and all my efforts to dig out more information on Garcia have ended in vain. As it does not hail from a famous UCLA alumni, the university does not host a public version of the film on their YouTube channel at time of writing, and the third-party print I did find is a heavily worn version, with an editor’s timecode hard burnt into bottom frame at all times. Our access to the film thus dangles by the same thin, readily-snipped thread as all singular uploads of obscure works by third parties, and its impossible to miss the glaring black-and-white sign the original 16mm print was lost decades ago, survived only by scans of an nth-generation copy not even officially available to the masses. For but the grace of Chimalli Media, we could have another With Car and Camera Around the World on our hands, something highlighted as important and worthy of preservation by the Library of Congress, yet totally unavailable because the people who hold legitimate copies hadn’t quite gotten round to prettying them up in time for the announcement (or since — Car and Camera remains AWOL for even private viewings nearly a year since our coverage).

Thereby, with the timecode right there in our faces front to back, I say why not embrace its somewhat awkward presence as the basis for today’s discussion? The subject under review deserves a piece reflective of the upset and outrage communicated through its structure, so I’ll use the timestamps provided to break Requiem-29 down piece by piece, describing the basic contents in each chunk and then outlining the context one might not so readily infer watching solo. Do bear in mind there’s a 40-some second discrepancy between the video’s timer and what you’ll see on the YouTube player, and that I am at all times referring to the former — you don’t wanna get lost in this discussion or somethin’.

TCR 00:46–03:44 — Television footage from the Los Angeles Coroner’s Office inquest into the death of Ruben Salazar (March 3rd, 1928 to August 29th, 1970), presided by Norman Pittluck. Pittluck begins the inquest with a short note of the facts about Salazar’s person, then requests a doctor on the witness stand describe a metallic missile in detail and affirm it as a weapon capable of inflicting an injury consistent with the blow that killed Salazar, which the doctor does on both counts. Between and after these scenes, handheld footage of mourners gathered at Salazar’s wake, lined up and mingling to comfort one another; the first of these is accompanied by a sorrowful Spanish song, the second by growing chants of protest from an exterior source.

As the picture never identifies him in detail: Ruben Salazar was a Mexican-American journalist who worked as an investigative reporter at the Los Angeles Times from 1959 to his death in 1970, progressing through the ranks as a resident foreign correspondent throughout the ’60s and earning a great deal of respect from his peers in the process. Towards the end of the decade, Salazar turned his reporting to domestic matters, specifically the growing Chicano Movement in the southwest United States, a civil rights push centered around granting disenfranchised Hispanic/Latin Americans a greater sense of unity under the self-selected identifier Chicano towards a goal of concentrated resistance against (among other matters) targeted police brutality, inadequate farmers’ rights, poor educational standards, bigoted economic policy, and the white-dominated systems which enabled all the above. Though middle-class and therefore not half so vulnerable to the circumstances and issues ravaging the poorer sectors of the Chicano community, Salazar’s willingness to actually cover racial front-facing stories in East LA without sensationalizing the area’s crime rates and attend Movement-aligned press conferences where others in the mainstream flaked exposed him to people and stories which influenced a shift in his coverage. He never became a radical himself or someone who’d call for dramatic, immediate change in his reports, but he wrote with an open mind and sympathetic bent towards the Chicano struggle unheard of in a non-independent reporter. This development made him known amongst colleagues as an excellent code-switcher, a journalist capable of attending upscale events with the elite or seeking out stories from the common folk in the barrio and relaying both in separate stories easily digestible to white or Chicano tastes.

A good thing too, as early 1970 saw Salazar leave his active position with the Times to serve as news director for KMEX, the largest Spanish-language news station in Los Angeles at the time. Through his efforts to reach Chicano populations through a medium more commonly consumed in impoverished barrios than print media, Salazar maintained some presence at the Times, writing weekly columns covering local (often Chicano) issues from January to the day before his late August death. For all this, Salazar’s was not a name commonly known to the people — known and respected by colleagues, yes, but not a household name, and not nearly prominent or respected enough to enjoy full protection as a journalist. Salazar’s positive coverage of Chicano issues often required less than flattering reporting on the LAPD’s activities, which led to him fearing a police tail in his final days and later reports from friends telling of insiders at the Times breaching journalistic ethics to feed the cops information about his person and activities. It was only after his death that Salazar became widely famous, as a martyr, a face on signs and banners and murals, a name evoked to call for immediate systemic overhaul in the here and now, someone of far greater radical leanings than he actually was. One might say it progressed to a point of obscuring the actual man as a wounded community understandably rallied around one of their own and elevated him to a face of La Causa. Public good comes out of his death at the cost of accurate remembrance. A tale too often told, a fate too often met.

If you notice I’ve skated straight past just how Salazar died, don’t fret — Requiem-29 also sees fit to not reexamine this subject for another twenty-five of its thirty total minutes, and with good cause too.

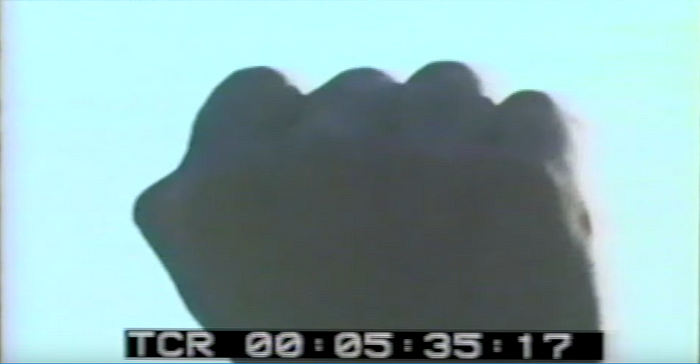

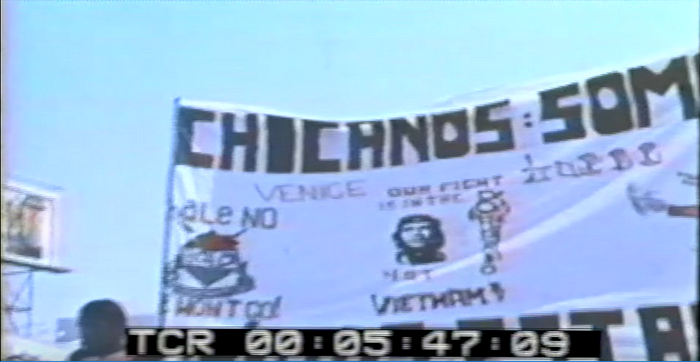

TCR 03:45–6:09 — Handheld on-the-ground footage from the August 29th Chicano Moratorium, depicting throngs of Chicano protestors marching through the streets of Los Angeles. Members of the Brown Berets can be seen amongst the crowd, marchers raising their fists in solidarity as we hear chants of “CHICANO POWER!” and cries of “LA RAZA!” Signs proclaiming “Brown is Beautiful,” “Indians of All Tribes,” and “Viva La Raza” pass by the camera. Tracking shots down Whittier Boulevard give us some sense of the event’s scale, while close-up on a raised fist and head-on shots of marchers with arms locked demonstrate the mass solidarity. Towards the end, the approach of a large banner gives us some idea what this is all about: Vietnam.

Prior to the Moratorium, the most prominent demonstration from the Chicano Movement in East LA were the 1968 Chicano walkouts, when thousands of students left school in a coordinated protest against lackluster educational standards for those of Mexican descent in the city. These walkouts were in part organized under the Brown Berets, a militant organization dedicated to community activism and gluing the disparate concerns of Chicano communities together under one umbrella. Two of their number, Rosalio Muñoz and Ramses Noriega, sought to expand the movement to include address of outrage over the body count of Chicano youth in the Vietnam War. As we’ve previously discussed, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s Project 100,000 push to increase ready boots on the ground by lowering physical and IQ standards for enlistment resulted in young men primarily from areas afflicted by poor economic and educational standards being shipped off to die on the front lines, unprepared and unfit for active duty. This in turn meant Hispanic youth, though represented at just 10% population across the southwest in 1970 and even lower nationwide, represented 20% of all Vietnam casualties. With public attention already called to the dismal state of education for Chicano youth, a shift to calling for a moratorium on an already unpopular and unjust war made an easy pivot. Thus, Muñoz and Noriega spent the months leading to August 29th organizing and conducting smaller marches in cities throughout the southwest in preparation for their biggest move of all. When the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War marched the three miles from Belvedere Park to Laguna Park, they attracted anywhere from 20-30,000 Chicanos, the single largest gathering of Latin Americans for one cause to date, only since surpassed by the 2012 protests against Arizona SB 1070.

TCR 06:10–08:16 — Women in traditional Mexican garb perform a flowing dance, and a band on-stage sings a many-voiced song celebrating the revolutionary spirit. We see the throngs of thousands watching the performance across many shots, not a single violent or seditious act visible amongst the persons stretched out across the entire park. Close-ups on individuals amidst the crowd enhance the total sense of unity and linked purpose, and provide a backdrop of serenity that will be broken momentarily.

The gathering at Laguna Park was meant as a peaceful thing, a celebration of Chicano heritage and culture mixed with speeches from community leaders and national activists calling attention to the issue overseas, and for a short time it was just so. This in spite of efforts from those Muñoz and Noriega would later identify as infiltrators planted by the LAPD and the ATF, both organizations determined to shift any large gathering of a minority population into full-blown riots so as to generate flimsy cover for their disproportionately violent retaliations and turn public opinion against any and all civil rights organizations. When efforts to corrupt the Moratorium from within prior to the march failed…

TCR 08:17–12:21 — The police march on Laguna Park. They are organized and deliberate in their movements in contrast to the now dispersed and panicking crowd. No inciting incident is shown as thousands flee from clouds of tear gas and marching lines of helmeted men, examples of violence purely on the cops’ part in these early moments as members break from the pack to beat on fleeing protestors, sometimes multiple men to one helpless body. Members of the community are most often seen detaching from the crowd to calm their fellows and prevent people from rushing the police line, and when protestors do throw things or rush a cop on a scattered individual basis, they are swiftly met with far harsher violence by officers who quickly move on to do the same on the heads of protestors who decidedly did not assault anyone. Arrests come into view as protestors and police lob canisters of tear gas back and forth. We cap the segment with an interview from a woman who seems completely shocked by the police assault, and stresses how they even tear gassed children.

…they turned to pressure from without. A short way into presentations at Laguna Park, the nearby Green Mill Liquor Store reported an incident involving several protestors who’d come inside for drinks after marching on a hot day. The owner opted to lock these people inside to ensure they would pay, and when they became restless as a natural reaction to being locked in when they just wanted a drink, management called the LAPD. For their part, the police had been uniformed, equipped, and assembled nearby hours prior, and arrived in force to not only break up the disturbance at the liquor store, but break up the entire Moratorium gathering. With billy clubs and tear gas and a press of unrelenting bodies, natch. Watching the footage as presented here, even understanding it is deliberately selected and edited to reflect a negative perception of the police department, the contents are fully consistent with reports the gathering did not turn violent until police intervention, and that police brutality against the gathered Chicano population far outweighed any instances of protestors rioting. Even when we acknowledge the existence of riots following tens of thousands of persons suddenly dispersed and assaulted by the full might of the local police department with little warning and no readily discernible cause, those examples are rather moot when you consider they find their roots in bigoted panic and preplanned strikes against a peaceful gathering. One should not and cannot blame the aimless and angry when they are aimless and angry because the powerful have shattered their sense of purpose and security in service of a higher oppressive agenda.

TCR 12:22–21:52 — We return to the inquest with several snippets of Pittluck interrogating a man about the events of the Moratorium. The focus of conversation in the first clip is a series of questions about whether the man saw people breaking police car windows, whether he saw the individuals breaking police car windows, whether he has any photos of people breaking police car windows, whether he saw anybody breaking SHOP windows along Whittier Boulevard, exhaustive to the point of redundancy. As the clip continues, the man becomes increasingly frustrated at Pittluck’s seemingly irrelevant line of questioning, and outright says as much towards the end. In the second, the man begins by expressing frustration at how limited he and his colleagues are in their ability to cover police matters when they are not recognized as a legitimate newspaper and so not afforded proper protection from police brutality, and spins this into a speech about how this line of questioning is more concerned with his personal integrity in presenting photos of the murder scene than questions directed at deputies presenting irrelevant photos of looters. The final clip begins with Pittluck grilling the man over minute details of a photo depicting police beating protestors and casting doubt on how he can ascribe any narrative to the photos. When Pittluck pushes to know where the man has stored his work following a lengthy description of a police raid on his offices, the man’s patience wears out entirely and he says what must be on everyone’s mind: this is clearly racially biased questioning, and has nothing to do with the death of Ruben Salazar.

The man on the stand for these nine minutes is Raul Ruiz, activist, photojournalist, and editor of La Raza, a publication dedicated in part to documenting the Chicano Movement and injustices against Chicano populations. He was likely called to the stand because he photographed a key moment seconds before Salazar’s death (a picture whose implications fuel doubt about the official story’s validity to this day), but as we see, a significant portion of his time at the inquest did not focus on what he saw of relevant events. The implications in Requiem-29 dedicating so much time to showing how Pittluck and the representatives of the inquest willfully wasted Ruiz’s time are clear: there was no interest in determining how or why Ruben Salazar died that day, only another front meant to demonize Chicano activists and paint an act of police brutality as senseless mob violence met with just force. Accounts of the sixteen day inquest like Hunter S. Thompson’s “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan” back up a view these nine minutes are representative of the entire hearing, a live televised series of tangents, rambles, and bigoted questions clearly intended to control the public narrative around the Moratorium, cut its legs out by playing on fears of looters and rioters without any intent of addressing the death the inquest was called to address. The sound of cheering as Ruiz makes his final presented statements tells us these views were not at all uncommon amongst those invested in the investigation.

TCR 21:53–27:16 — An interview with Ruiz after the fact, outlining the numerous ways in which the inquest has failed to hold with proper conduct in a long stream of conscious fashion. Lack of focus from the overseer, the District Attorney’s office acting in an inappropriately defensive capacity for a supposed objective party, allowance of wholly unrelated evidence for the simple fact it makes the marchers look bad, disallowance of La Raza sources as evidence, red-baiting the community over “Viva Che” signs half-glimpsed in the corner of photos. This last prompts a break-in of footage from the inquest in which Ruiz defends Che’s character and reputation in the Latin American community after Pittluck asks if he was “Mister Castro’s man.” At the tail end, Ruiz again expresses frustration with the obvious bias and agenda of the inquest, stating, “As of the second day of this inquest, this inquest has ceased to really function as an investigating body for finding out the facts of Ruben Salazar, and right now they’re simply trying to throw some reflection on the community, which is going to deviate itself from the real issue at hand: who murdered Ruben Salazar?”

Any regular reader of Registering the Registry or body with an interest in 20th-century-and-onward American history ought not feel any surprise at the nature of this besmirching colorization of minority protestors and civil rights activists from law enforcement officials and the mainstream press — we’ve seen it too many times for it to prove much novel. It does, however, still provoke a sense of disbelief and indignation at how the death of an innocent man, a man who cared for his community and his people, a man whose only possible wrongs were reporting what was going on in language too plain and easily understood for the comfort of the powerful he covered, could be so easily and callously swept aside in an official hearing about his death in favor of promoting fears about dirty communist Mexican rabble-rousers destroying property. Replace “Mexican” with any minority boogeyman you like, and the muckflinging of that statement is basically a regular feature of right-wing nightly news and social media messaging now. Requiem-29 stands as a direct document of injustice in action, a firsthand account of how a peaceful protest was mischaracterized into ammo for a cheap culture war by representatives of the Los Angeles and United States governments, and it only becomes all the more so when it makes a hard and impactful cut to…

TCR 27:17–30:24 — Deputy Tom Wilson takes the stand and describes his actions on August 29th, how he approached the Silver Dollar bar without much interest in what sort of tear gas canister he was using, readied his weapon at chest height, and angled his shot upwards so it would bounce off the ceiling and reach the back of the building before lobbing a second non-projectile canister as follow-up. He is then handed a weapon and spends several minutes mishandling it against Pittluck’s adjuring before confirming it is the weapon he used that day. During this, we are shown a close-up of Ruiz’s photo of Wilson outside the bar.

…the man who murdered Ruben Salazar.

It was like this. Salazar and his crew from KMEX had come out to cover the Moratorium and spent several hours ranging across the city to gather information on the police attack as it radiated out from Laguna Park. At the Silver Dollar bar some three miles from the park, Salazar and company stopped inside to use the restroom and have a small cooldown beer before heading back to the office. As he sat down with his drink, a contingent of sheriff’s deputies came along — police reporting initially claimed Salazar was shot by an unknown sniper, then changed their tune to justify Wilson’s actions by claiming they had probable cause to flush out a pair of gunmen (who no witness could remember) and gave audible warning for people to get out (despite Ruiz’s photograph showing and witness testimony supporting him herding people back inside). However one likes to believe, Wilson then did exactly as he describes in the clip. What he leaves out is: the projectile he fired (the one examined by the doctor at film’s open) was one meant for breaching heavily barricaded structures, fired through an open window covered only by a thin curtain completely incapable of halting the missile’s momentum, chosen after Wilson and his men had glimpsed Salazar entering from outside, angled upwards just as Salazar stood up. The canister struck him in the head, killing him instantly. The police unloaded so much tear gas into the bar, Salazar’s body was not discovered until hours later, and his colleagues only learned of his death when it was mentioned in passing on a major news channel.

I am rather of a mind with Hunter S. Thompson in “Strange Rumblings” on this one. Even if we discount all suspicion Wilson or higher forces in the LAPD preplanned Salazar’s death, even if we go further and whole-heartedly accept Wilson did not consciously target Salazar for his negative coverage on the police or at least acted rashly in the heat of the moment, the killing and its fallout speak to something far more terrifying than conspiracy to cut down a journalist. It speaks to an incompetent closed circle of authoritarian brutes so mismanaged and sloppily checked that one of their number could kill one of the few journalists willing to hold them accountable with the experience and clout to back his words, and the higher-ups will still scramble to his defense despite being caught out in lie after lie, simply because impulsive manslaughter proved convenient. Such misplaced solidarity amongst authorities carries grimmer portent when born from ineptitude instead of cunning.

The coroner’s inquest did not find Tom Wilson guilty of any wrongdoing in the death of Ruben Salazar, and subsequent investigations into the case over the last fifty years have repeated this finding while still refusing to hear evidence consistent with Ruiz and La Raza’s findings. The Chicano Moratorium Committee would eventually fall victim to outsider sabotage of its goals, the Brown Berets would disband in 1972, La Raza would cease publication in 1977, and the Chicano Movement writ large would decline in influence throughout the ’70s. Requiem-29 would slip into obscurity, cited in textbooks but not widely watched or discussed. Laguna Park is now Salazar Park, a change consistent with dozens of other locales and institutions rechristened in his honor, but Ruben Salazar is and will always remain dead too soon, his voice silenced regardless whether his killer meant to shut him up.

It is easy to despair at all this, to forget what progress has been made in the decades since August 29th, 1970, to think nothing will ever meaningfully improve. Though one can point to measurable improvements amongst the Chicano community in all this time, the basic issues and underlying casual bigoted causes remain in place, and those of Hispanic descent still occupy a secure and steady place on the ever-turning wheel of Roots Of All Ill In America alongside those of every non-white race, every non-Christian creed, every non-binary political movement, every non-wealthy class, every non-male sex, every non-masculine gender, every non-straight orientation. The wealthy and powerful who are comfortable with the status quo by direct profit from the continued suffering of others sit prettier and cozier than ever in the 2020s because, for the civil rights gains of events like the Chicano Moratorium and the larger Chicano Movement, they have also learned how to avoid the messaging mistakes of the past and tighten their control of the narrative. Everyone who doesn’t fit an incredibly narrow definition of The Right Kind Of American sits in the sights, and that definition is prone to further narrowing or making guarded exceptions at first convenience if it means maintaining control a second longer. It is easy and natural to despair at all this, to sink into anger and desire for directionless retribution for the sake of seeing SOMETHING change, even if not for the better.

This must not be where our processing ends.

TCR 30:25–31:50 — Ruiz says the following over slow-motion footage of the protestors marching towards the camera, flags commemorating La Causa and La Revolucion sliding by in slowmo, the throngs of Brown Berets and average Chicanos alike walking proud and tall: “In reality, the rights which people think that they have are no longer really there. The rights which they supposedly thought they had had, hopefully as a results of this inquest, they will understand that as Chicanos they really have very few, and they must begin to look to themselves for the strength, for justice among themselves, because there’s nobody else going to help us, absolutely nobody.” The audio transitions into a drum and horn anthem as the picture ends.

He is right. Each vulnerable population within the United States must band together, better understand the total nature of their problems, extend compassion and helping hands to those of their lot in more vulnerable positions, and work to ensure the locked-arms and brick walls of the powerful cannot continue their centuries long exploitation. A glimpse over retrospective resources on the Chicano Moratorium readily shows the Chicano community has continued the work of educating the world and learning from their own history — of those I consulted for this article, I most recommend the LA Times’s 50th anniversary retrospective series, the Library of Congress’ resource guide hub, and the LA Conservatory’s 50 Years Later presentation. This is good and right, and illustrates a generation grown stronger for the ills of their past. There must, however, also be a modern intersectional view on the problem, unity and understanding and coordination betwixt all populations targeted as scapegoats and used to trick less engaged citizens into furthering their own repression. If the underclass of America is to stop voting against its own interests and effect genuine, tangible change, the sort of solidarity seen in Requiem-29 must be common amongst all races, creeds, ideologies, classes, sexes, genders, orientations, disabilities or languages or ethnicities or however you want to divvy and categorize Americans; there’s a million ways to chop us up and separate us out, and we must recognize the common vulnerability to fearmongering and manipulation about those who are deemed other and lesser for it. Either we remain strong, continue the work and struggle in a focused manner for long as non-violent retaliation remains viable, or we have lain down and died already. Simple as.

***

And if we are to chase this goal, it must not be only my voice speaking. What are your thoughts on Requiem-29, be they on its construction, message, the history it portrays, or the vulnerability of lesser-known films’ public accessibility? Has it out in the comments and I will see you two weeks hence for another documentary about a death associated with the Civil Rights Movement. An effort to document and distribute the work of Illinois Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton turned into private investigative journalism when Hampton was killed mid-production, a death director Howard Alk and producer Mike Gray soon discovered was the result of police conspiracy. We’re talking about 1971’s The Murder of Fred Hampton, which may be watched courtesy the Chicago Film Archive here. I’ll see you then.

Gargus may also be found on Letterboxd, tumblr, twitter, ko-fi.

Registering the Registry is sponsored by Adept7777 and Dan Stalcup on Patreon.